What Happened to Comanche the Horse After the Battle of the Little Big Horn?

‘The horse known as “Comanche” being the only living representative of the bloody tragedy of the Little Big Horn, ... his kind treatment and comfort should be a matter of special pride and solicitude on the part of the 7th Cavalry, to the end that his life may be prolonged to the utmost limit.

The Commanding officer ... will see that a special and comfortable stall is fitted up for Comanche. He will not be ridden by any person whatever under any circumstances, nor will he be put to any kind of work.’

By Command of Colonel Sturgis

7th US Cavalry

April 10, 1878

Little Bighorn country: Ranchlands and Prairie Near the Battlefield.

(Image: Boyd Norton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Source:

🔗)

So, after his ordeal at the Battle of the Little Bighorn and recovering from his injuries, Comanche was to live a pampered and cosseted life — according to Colonel Sturgis. But how did this edict play out in practice?

According to eye-witness accounts, things started well for Comanche. Not only was he stabled in a ‘spacious and comfortable stall,’ but the gate was never closed and he was allowed to wander about the camp at will, ‘loose to graze and frolic as he wished.’

He became such a favourite he was even dubbed the ‘second commanding officer.’ Being ‘a great pet of the solders,’ he was inevitably spoiled. Buckets of beer and bran mash infused with whiskey were frequent treats, and he never refused a sugar lump.

Such was his status, that whatever the mischievous behaviour: grazing the parade ground and depositing the results of the digestive process thereon, trotting over and leading a troop as they went through their drills, teasing other horses tied to the picket line, he was never chastised.

He ate the sunflowers in the officers’ gardens. He hung around the canteen begging for morsels. He overturned garbage cans looking for dainties. After a particular circuit of the garbage cans he returned back to the stable with his head covered in coffee-grounds and other trash-can detritus.

Comanche and his personal attendant Pvt Gustave Korn formed a close attachment, to the extent Comanche followed him about like a faithful dog. Comanche even tracked him down to the house of a ‘lady friend’ and stood outside neighing and stamping until Gus came out, possibly snapping up his suspenders. That ruckus must have been a good bit exasperating if conjugalities had reached an advanced stage.

Comanche with attendant Pvt. Gustave Korn, Fort Abraham Lincoln, June 1877.

(I would love to supply an attribution for this image, which I found online, but cannot find any information about it.)

On a more sombre note, on June 25th every year, his tack was polished and he was draped in black. A saddle was placed in reverse on his back, likewise a pair of boots in the stirrups, and Comanche led the parade to commemorate the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Was Comanche Ridden Again?

This is difficult to answer. A rumour persists that two ‘ladies of the post’ (officers’ daughters) vied with each other to see who got to ride him most.

More surprising is that the equine hero of the Little Big Horn went out on campaign again, accompanying the Seventh on various expeditions and actions on the Dakota and Wyoming plains. In the latter months of 1878 the Seventh covered over 1200 miles in scouts and skirmishes, and Comanche performed admirably.

It is unclear if he was ridden, but it seems odd to take the famous horse out on campaign, with the inevitable dangers and his need for fodder and care, just as a spectator.

Comanche at Wounded Knee

A little-known fact about Comanche: he was present at the Seventh Cavalry’s engagement with the Lakota at Wounded Knee (1890), now generally considered to be a massacre and the final act in the subjugation of the Plains Indians. Comanche took no part in the action.

Interestingly, his life as a cavalry mount (1868-91) covers virtually the whole post-war period of campaigns to defeat the indigenous peoples of the Plains.

Comanche’s Death

His devoted attendant and ‘friend’ Gustave Korn was killed at Wounded Knee. The old horse was never the same again. He is said to have ‘mourned continuously’ and to have become ‘morose’ and have ‘but little interest in life.’

On November 6 1891, suffering from colic, Comanche died. He was around 29 years old. The farrier Samuel J Winchester cared for him to the end, ‘while I had my hand on his pulse, and looking him in the eye.’

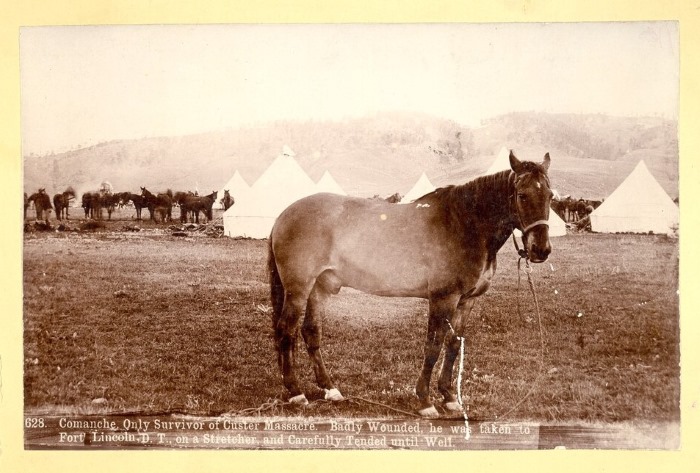

Comanche the very old horse c. 1890, shortly before his death.

He seems not very interested in the photographer because his ears are pointed backwards, and he doesn't want to go anywhere because he is standing

on his tether rope.

(Unknown Photographer (Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument) NPGallery, Public Domain;

CC: 🔗)

Comanche gives his own account of his convalescence and celebrity, straight from the horse’s mouth so to speak, in Comanche Is Not My Name Part 2. Here is an excerpt:

‘After the big fight they made me celebrity. I got pampered worse than a Comanche’s favourite buffalo horse and told I’d never again be compelled to charge into bloody battle.

I got invited to fetes and parties, Sunday school openings, was fed apples and carrots, them latters always a let-down when you is anticipating the formers and I judge it an act of cruelty. I got slapped by gubernators and petted by spinsters and pinched by shavers and my picture took. By God, this life gets more irksome than a body can bear.’

Sources:

Elizabeth Atwood Lawrence, His Very Silence Speaks (1989)

Peter Cozzens, The Earth is Weeping (2016)

Albert Winkler, ‘The Case for a Custer Battalion Survivor: Private Gustave Korn’s Story.’

Montana: The Magazine of Western History (2013). Accessed 11.2025 here