Comanche Brutality 1:

Popular Perceptions

‘‘Red devils... Blood-thirsty monsters.’

‘Implacable killers, grim apostles of darkness and devastation.’

A 19th-century and a

21st-century appraisal of the

Comanche in the Frontier days (see nt. 1).

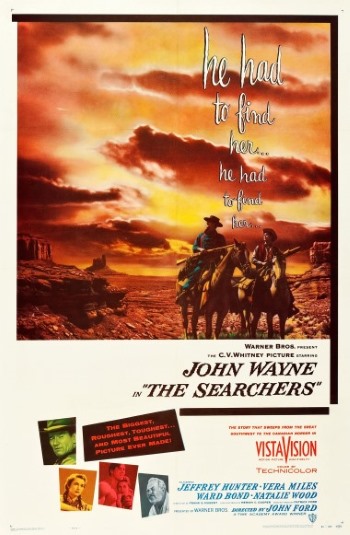

John Wayne is angry.

More than that, John Wayne is distraught, in despair. He even pulls a lance out of a dead cow

and hurls it into the desert to demonstrate his despair. A rare emotional state for The Duke. But it's not down to the dead cow.

Wayne is hard-as-nails Civil War veteran Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (1956). The dead livestock is a decoy; the lance of a type carried by only one tribe—not the Caddoes or Kiowa—but by the dreaded ‘Comanch,’ and they're en route to strike his brother Aaron's idyllic family homestead.

Ethan arrives too late. The ranch is ablaze, most of the family slaughtered. Ethan finds a shred of clothing belonging to Aaron's wife — and finds what's left of her in the barn. We are left to imagine what the savages have done to her. Neither is the family's adopted son Martin (Jeff Hunter) allowed to see. Rather than let him enter, Ethan punches him in the face.

‘He had to find her... he had to find her...’ 1956 Poster for The Searchers.

(Image: Bill Gold, Public domain, Wikimedia Commons. Source: 🔗)

Hard to imagine in all this carnage, but Ethan discovers something far worse: the Comanche have kidnapped the two daughters, Lucy and Debbie. Ethan is soon on the trail. Lucy is discovered murdered and, by implication, raped. Ethan and Martin set off on a quest to save Debbie. But they have different ideas of what this ‘saving’ might look like.

For Ethan Debbie is finished, consigned to a fate worse than death, to be the ‘leavin's of Comanche bucks.’ Now ruined for civilized society, if Ethan finds Debbie, he will kill her. After all, living with the barbaric Comanche for eight years (notwithstanding all the hair and beauty products they appear to possess) it’s kindest thing for all concerned.

The Searchers: the denouement. Martin shields Debbie from Ethan

(Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=456116 Source: 🔗)

Recent literary depictions of the Comanche plough a similar furrow.

For Larry McMurtry in Comanche Moon (1997) and Philipp Meyer in The Son (2013), despite both authors giving a more rounded portrayal,

the Comanche are still pitiless child killers, rapists and gleeful torturers.

Again in cinema, as late as 2017 and Hostiles, when renegade Indians attack homesteader Rosalee Quaid (Rosamund Pike) and family, kill and scalp her husband and murder her three children, who are the culprits—even though they’d been defeated for nigh-on twenty years?

You've guessed it.

What about popular history. In Empire of the Summer Moon (2010), for S. C. Gwynne Comanche brutality is an ineluctable fact. He highlights gang rape as a particular predilection of the ‘filthy and bug-ridden’ Comanche, a ‘very advanced form of evil’ (nt. 2). Gwynne goes on:

‘If the Comanches were better known for their cruelty and violence, that was because, as one of history's great warring peoples, they were in a position to inflict far more pain than they ever received.’ (p. 57).

Detail from Comanche Trying to Lance an Osage Warrior, George Catlin, 1834.

(George Catlin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Cropped. Source: 🔗)

Wow. That's some statement.

Instead of interrogating the Comanche's unparalleled reputation for brutality, Gwynne tries to understand and explain it. Brutality is a result of their highly individualistic religion focussed on extracting ‘puha,’ personal power, from the supernatural. Brutality is a product of their backward, nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle – in contrast to the progressive Euro-American agrarian.

In other words, European settlers had enjoyed the benefits of Christendom, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution, with all their philosophical, technological and scientific advances. The Comanche, they were still back in the Stone Age. (nt. 3)

How Did This Reputation Originate?

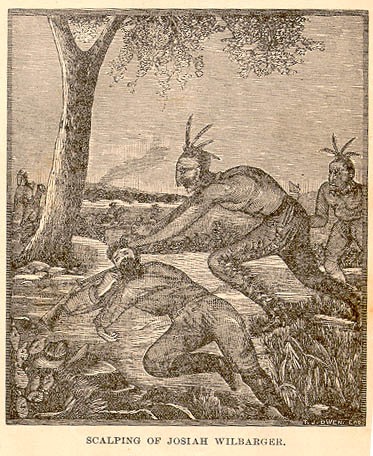

Let's consider a couple of of main sources: Captivity Narratives, and John Wesley Wilbarger's Indian Depredations in Texas: Reliable Accounts of Battles, Wars, Adventures, Forays, Murders, Massacres, Etc (1890), a book considered to be ‘a classic work of Texana’ and reprinted many times. In it, Methodist minister Wilbarger (1806–92) meticulously recorded over 250 Indian raids and clashes.

Personal experience may have been the motivation for his exhaustive compendium. In 1833, Indians attacked Wilbarger’s brother, Josiah, scalped him and left him for dead. Understandably then, John Wesley developed at best a jaundiced view of Texas’s native inhabitants. He is the author of, ‘Red devils... Blood-thirsty monsters’ cited above, and unapologetically describes the measures taken against the Comanche as, ‘a war of extermination.’

(Image: The scalping of Josiah P. Wilbarger. Public Domain; Texas State Library and Archives Commission CC: 🔗)

We'll return to Wilbarger later.

As for Captivity Narratives, in America these date almost to when the first colonists settled in New England and the inevitable clashes with indigenous peoples.

Indians took prisoners and vice-versa.

When white captives were ransomed, some wrote down their experiences and had them published. A couple of 17th-century examples from King Philip's War are:

A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (1682),

Humiliations follow'd with Deliverances (1697), (an account of the capture Hannah Duston.)

A bit like thriller-chillers and misery memoirs nowadays, Captivity Narratives became a hugely popular literary genre. Mrs Mary Rowlandson's narrative flew off the shelves on both sides of the Atlantic, and has been called ‘the first American bestseller.’ For a while, only the Bible outsold it. Hannah Duston's story, republished numerous times, was also a big seller, no doubt aided by the account of her personally hacking to death four of her captors, six of their children—and scalping them.

Hannah Duston Killing the Indians, 1847

(Painting: Junius Brutus Stearns, Public domain, Wikimedia Commons. Source: 🔗)

Captivity Narratives became so popular that down-at-heel ‘penny dreadful’ authors wrote entirely fictional narratives to cash-in on the trend. Burnings at the stake and infants dashed against trees were stock features.

The profitability of Captivity Narratives really ought to be kept in mind when considering then as historical sources. ‘I got kidnapped by the Indians, and they made me do a bunch of boring chores,’ wouldn't shift much product.

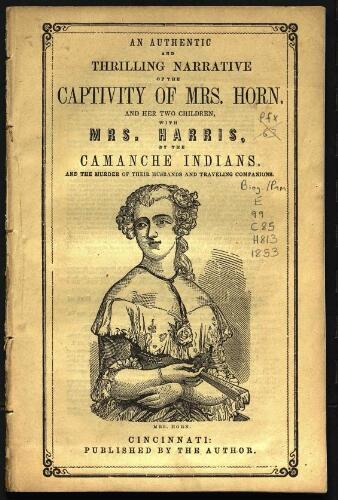

Narratives by captives of the brutalissimo Comanche include:

Sarah Horn, A Narrative of the Captivity of Mrs. Horn, and Her Two Children, with Mrs. Harris, by the Camanche Indians. (capt. April 1836; pub. 1839)

Rachel Plummer, Rachael Plummer's Narrative of Twenty One Months' Servitude as a Prisoner Among the Commanchee Indians (capt. May 1836; pub. 1838)

Dolly Webster, A Narrative of the Captivity and Suffering of Dolly Webster Among the Comanche Indians in Texas, With an Account of the Massacre of John Webster and His Party (capt. 1839; pub. 1843)

Nelson Lee, Three Years Among the Camanches (poss. capt. 1855 [?]; pub. 1859)

Dot Babb, In The Bosom of the Comanche (capt. 1865; pub. 1912)

Clinton Smith, The Boy Captives (capt. 1871; pub. 1927)

Title Page from the Sara Horn Narrative

Now, a few Indians in these memoirs were grudgingly portrayed as noble and even merciful. Some captives even developed a familial affection for the their captors (See Cynthia Anne Parker, below.) But Nelson Lee's opinion above typifies the picture of native peoples these memoirs convey.

For Mary Rowlandson, her captors were,

‘hell hounds... merciless heathen... ravenous beasts... who rejoyced in their devilish cruelty.’

Rachel Plummer related of the Comanche,

‘They appear to be very fond of human flesh. The hand or foot, they say, is the most delicious.’

For the editor of Dot Babb's memoir the Comanche were,

‘The most unrelenting savage barbarians that ever trod the earth, an unrestrained, inhuman, savage debauchery crying aloud for the intervention and mercies of God and man,’ who, ‘struck with the fangs of the most vicious, merciless, and unreasoning beast, ... in their unrestrained and unresisted madness and ferocity.’

For Sarah Horn,

‘inhuman wretches ... a dark mass of depravity’

Politician, newspaper editor and Texas Ranger Rip Ford wasn't a Comanche captive, but he had plenty of battles with them— and it's a safe bet he'd be familiar with the narratives. In trying to raise more resources to defeat the Comanche he declared,

‘Our people have been tortured in the most inconceivable and brutal manner by our savage foes. Women have been violated in the presence of their husbands—daughters have been ravished in the presence of their Mothers—children have been carried into a captivity infinitely worse than death.’ (nt. 4)

Upshots and Repercussions

So, the Comanche: serial rapists, bestial cannibals, baby killers, demonic torturers and mass murderers—heathens to boot— at this point it's all looking bleak for salvaging something positive from their barbaric reputation. What can we say?

Let's begin with this.

For native peoples what might be the upshot of this welter of negative optics?

Allow Euro-American settlers to express it:

‘An extirpation [of the Indian] would be useful to the world, and honorable to those who can effect it’ (1782)‘Such monsters of barbarity ought certainly to be … hunted down as wild beasts, without pity or cessation.’ (1815)

‘This country was designed for a more noble purpose than to be a harbour for those rapacious savages, whose manners and deportment are not more elevated than the ravenous beasts of the forest’ (1813)

‘It seemed to be a heartfelt desire of every person.

Exterminate the Indians,was the watchword.’ (1860)‘RESOLVED:

To select twenty-five men to go Indian hunting, and all those who can fit themselves out shall receive a nominal sum for all scalps they may bring in ... That for every buck scalp be paid 100 dollars, and for every squaw scalp 50 dollars, and 25 dollars for everything in the shape of an Indian under ten years of age.

That each scalp should have the curl of the head, and each man shall make an oath that said scalp was taken by the company’ (nt. 5)

I'm not going to win any prizes for originality here, but I've changed the font so I'd better run with it.

The Comanche people had no written culture.

Captured Comanche women and children wrote no memoirs.

Settlers of European descent wrote all the contemporaneous accounts of outrages and depredations.

(nt. 6)

Settlers wrote no negative context of a raid, for example, any prior incident that might have provoked the attack.

So when reading such one-sided history, it is always worth asking:

What were the motives of the writers and publishers of such literature?

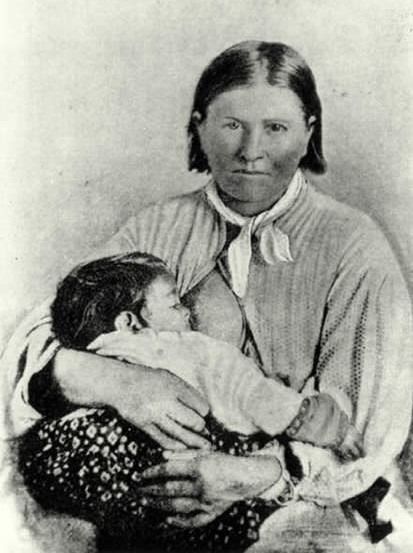

Perhaps the most famous Comanche captive, Cynthia Anne Parker (c. 1825—c. 1871)

In 1836, aged around ten, Cynthia was captured and spent twenty-five years with the Comanche.

She married a Comanche chief, and they had three children.

She was offered numerous opportunities to return to white society, but always refused.

In 1860, Texas Rangers attacked her village and she was taken prisoner, later recognised, and returned to her white family.

Cynthia subsequently made several unsuccessful attempts to escape back to her Comanche family.

Cynthia Anne Parker did not write a Captivity Narrative.

(Image: Uploaded by Leufroy at English Wikipedia. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons. Source: 🔗)

Coming Next

The Comanche were a warrior society.

Undoubtedly the Comanche raided. They killed; they burned homesteads; they stole livestock, kidnapped women and children and traded them.

Their economy depended on it. Acts of brutality must have taken place.

But taking into account the violent and dynamically changing world they were born into, were they really any different from anyone else?

Time for Part 2 of the blog: Comanche Brutality: Context (soon!)

Notes:

1: From Wilbarger, 1890; and Gwynne, 2010.

2: By contrast, both Tate (1994) and Anderson (2005) argue that rape was the exception rather than the rule.

There'll be more on this in a later blog.

I can't resist including Dan Flores's precis of the popular view of the Comanche here, ‘An anarchistic mob of hell’s angels on horseback...’

Caprock Canyonlands, 73.

3: The trader Josiah Gregg travelled extensively through Comancheria in the 1830s & 40s. He knew the Comanche well and observed,

‘These neither cultivate the soil nor live in fixed villages,

but lead a roving life in pursuit of plunder and game, and without ever submitting themselves ... to those fixed habits, which must always precede any progress in civilization.’

4: The quotation is from Tate.

5: The first three quotations are found in Derounian-Stodola & Levernier; the fourth is in Wilbarger;

the Scalp Hunt Resolution is in Dodge.

6: I am echoing the words of Herman Lehmann here. Quoted in Zesch he says,

‘the Comanches don't keep books and their side of history has never been written.’

Sources:

Anderson, Gary Clayton, The Conquest of Texas (2005)

Babb, T.A., In The Bosom of the Comanches (1912)

(found here)

Derounian-Stodola & Levernier, The Indian Captivity Narrative 1550-1900 (1993)

Dodge, Richard Irving, The Plains of the Great West and Their Inhabitants (1877)

Gateway to Oklahoma History

Flores, Dan, Caprock Canyonlands (1990)

Gregg, Josiah, Commerce of the Prairies Vol. II, 4th edn. (1849)

Gwynne, S.C., Empire of the Summer Moon (2010)

House, E., A Narrative of the Captivity of Mrs. Horn, and Her Two Children, with Mrs. Harris, by the Camanche Indians. (1839)

(here)

Handbook of Texas

Lehmann, Herman, Nine Years Among the Indians 1870-1879 (1927)

Newcombe, W.W. Jr., The Indians of Texas (1961)

Smith, Clinton L. & Jeff D., The Boy Captives, ed. J. Marvin Hunter (1927)

Tate, Michael L., Comanche Captives: People Between Two Worlds (1994)

(here)

Wilbarger, J.W., Indian Depredations in Texas (1890)

Zesch, Scott, The Captured (2004)

Comanche Is Not My Name

And now for the plug.

It is not giving away too much of the plot to reveal that Comanche the horse,

the ‘one and only living survivor of the Battle known as the Little Big Horn,’ and the hero of Comanche Is Not My Name, is himself kidnapped by the Comanche. In Part 1, My Jeopardacious Life on the High Plains, he gives his own account of the experience and in the telling, humanises the Comanche.

Here's a snippet. We pick up the story just after the camp women have shown mercy to a captive:

‘Now I picture you savvy types corrugating your noses at that latter episode. Why, don't he know the Comanche was the vilest, most pitiless, most bloodthirsty and butcherous savages whatever stalked the high plains. They’d take a man alive just so they could delight in excising his privy member and combusting his extremities, tie him upside down to a waggon wheel and split his belly and unwind a gut and stake it out for his eyes to contemplate, made it into a goddamn theatrical presentation. They roasted and ate their mortal foes alive, sacrificed their children to heathen gods and chawed on the tender parts. Ain’t this joker read the goddamn history books?

Apropos them character slurs, I never met the whole Comanche Nation and can only speak of my experience with this diminished bunch, and we was short on the waggon-wheel side anyhow. But I’ll admit, there is always bad apples.’